Welcome to the weekly reread of Katherine Kurtz!

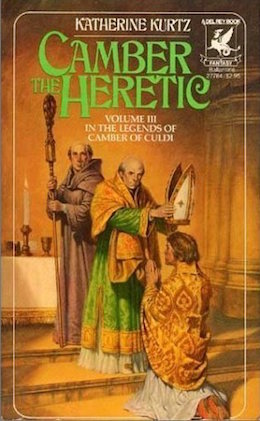

Last week we finished Saint Camber with, as it says on the tin, the sainting of Camber and further rumblings about trouble coming. And Cinhil rode off, glittery-eyed, into the night. This week we begin Camber the Heretic.

Camber the Heretic: Prologue and Chapters 1-3

Here’s What Happens: As noted in comments on the previous book, this is a much longer, thicker, tinier-printed book than its predecessors. But! I notice quotation marks on every page I’ve riffled through, so it’s maybe not as heavy on the synopsis as Saint Camber. I hope so. There are a lot of loose ends to tie up, and a lot of promised disasters to get through.

We begin with a Prologue, and already the plot is nice and thick and getting chewy. Three men are reading a document that “he” is guaranteed not to sign—but, declares a nasal-voiced person named Murdoch, he has! It was slipped into a stack and was signed with the rest. It’s the good old “sign ’em blind” maneuver.

And there’s a very good sign for the derring-do to come: one of the men goes by the epithet of Rhun the Ruthless. This is fun already.

Cullen hasn’t seen the document, either, and now we discover what it is: it’s the king’s will and testament. This conspiracy of three has just determined the direction of the regency after the king dies.

Which will be soon. Jebediah has gone to fetch Cullen at Grecotha. Rhys has been keeping Cinhil alive, but the conspirators don’t think he can manage that much longer.

And then Murdoch curses the “miserable Deryni,” which tells us they’re all human. It’s finally begun. The humans are making their move.

The meeting disperses. The third man, we discover, is an earl named Tammaron Fitz-Arthur, and he’s lining himself up to be the next Chancellor of Gwynedd. (An office, be it noted, now held by Bishop Cullen.)

Next scene, a few days later: we’re reintroduced to Camber, aka Bishop Cullen, and we get a precis of his receiving the king’s message. Cinhil is sick but still imperious, and he needs Camber/Cullen before Twelfth Night. Something is going on.

Camber spends some time in internal monologue, filling in past events and wondering what Cinhil wants. Maybe something Camber has been trying to get for years. He’s worried. Cinhil’s heir is only twelve, which means council of regents. Which could be good, or could be very bad. And Camber (aged seventy, disguised as sixty, acting like fifty—he’s our superhero to the end) has a bad feeling. The humans are going to turn on the Deryni. And he is determined to do something about it.

Chapter 1 begins about a month later, at the end of January, with Rhys in a quandary. The Earl of Ebor has had an accident, and Rhys hasn’t been able to heal him. Cinhil insisted on the strongest terms that he try. So he’s in Ebor, and Cinhil (still hanging on) is in Valoret with Camber.

The Earl is a Deryni and an ally. He’s also a member of the Camberian Council, which has been founded since the events of Saint Camber (small reader-snarl here; you’d think that would be a thing for an actual book), which is very very secret and has been working very very hard to revive lost Deryni knowledge.

That seems to be relevant to the Earl’s condition. He’s gone mad with magic.

Rhys is completely stumped. He and Evaine haven’t been able to do anything to help. Nor can Rhys come up with a diagnosis.

He and Evaine discuss what to do. We get a quick re-intro to Evaine, and learn that she now has three children and still looks like a teenager. Then Rhys gets to work.

He calls in the Earl’s “olive-skinned” son Jesse, who is extremely leery of his father’s powers, and a group of servants, and instructs them to hold the Earl down. It gets a bit wild, with flying swords and crockery, but Rhys gets a sleeping drug into him. When he’s well under, Jesse explains how the Earl was injured by a stallion.

Rhys and Evaine get back to work, in detail, with magical healing. Evaine finds the probable cause of the brain issue: the mark of a kick. Rhys goes back in, psychically, and in short order declares that “he’s going to be all right now.”

He and Evaine continue to tend the Earl as he comes to. The Earl is horrified to hear that he fought them—and even more horrified to discover that he’s lost his powers.

Rhys investigates, in detail, and it’s true. They’re completely gone. He and Evaine speculate as to what happened, then he goes down deep and finds the spot he turned off when he was healing the brain injury.

Camber needs to see this, Rhys says when he comes back out. Evaine points out that her father won’t want to leave Cinhil—and how are they going to tell him why they need him?

Rhys has an idea. They’ll send a message by courier, with a coded segment that will be sure to get Camber out there. (No Transfer Portal? Um, plothole?)

Chapter 2 shifts to Cinhil, who is still alive and apparently suffering from consumption—something with the lungs, certainly (though if it’s cancer, that would probably explain why Rhys can’t cure it). He and “Cullen” are playing a board game. Camber, of course, is winning. Cinhil is petulant. “Do you have to be so bloody good at everything you do?”

This reader wonders the same thing, rather frequently.

Cinhil keeps on kvetching while Camber keeps a close eye on him and gives us a re-intro to Joram, who like all the rest of the family hasn’t changed a bit since the first book. This chunk of exposition is rather convoluted as we get the whole summary of Camber’s long con and his family’s role in it. Naturally it has to keep on going because the next reign needs “Cullen,” too.

Cinhil makes another move and Camber is about to (brilliantly, of course) counter it when there’s a knock at the door. It’s Earl Murdoch, whom Cinhil likes and trusts and believes is virtuous. He’s cranky now, and he’s an anti-Deryni bigot who Does Not Like Joram or his (supposedly late) father.

Murdoch has come to report on the princes’ academic progress. He’s rude to Camber. Camber is all maddening sweetness in response.

Murdoch settles in with some minor drama and gives his report. He’s all praises for Alroy and Rhys, but he ignores Javan until Cinhil presses him. Javan is the crippled twin. Joram, who has been the boys’ tutor, is rather partial to him.

Murdoch is a rampant ableist. No cripples are fit for the throne, he declares. What’s more, Javan’s current tutor, Lord Tavis, is Deryni, and that is Not A Good Thing.

Cinhil stands up for Tavis. Murdoch continues to lean on Javan’s disability and “that Deryni”’s poisoning his mind against good human men such as Lord Rhun (the Ruthless, whom we have met).

Camber calls him on his bigotry. Murdoch triples down on the horribleness of Deryni—they murdered Cinhil’s family. He wants Deryni out of the nursery.

This puts Cinhil in a difficult position. Camber realizes the king has never lost his mistrust of Deryni. But he can’t say anything (though he thinks a great deal). He wills Cinhil to stand up for the Deryni.

Cinhil maybe starts to, but has a coughing fit. He recovers and asks for a moratorium on the Tavis situation, noting that Javan pined the last time Tavis was sent away. Murdoch accuses him of coddling his son. Cinhil holds his ground and then forgives Murdoch—to Camber’s dismay. Cinhil isn’t making any attempt to see through Murdoch’s facade of sycophancy.

Cinhil sends Murdoch away. He is not happy, especially since “Alister” gets to stay. Camber calms Cinhil down and notices he’s been coughing blood.

Joram also notices. Cinhil stops him before he speaks. He needs to talk to both of them about Javan—but is interrupted by another knock on the door. It’s Rhys’ messenger from Ebor.

Camber takes his time opening the message and informing the others what it says. Gregory will be fine, he says, but is insisting he come to give Last Rites. Cinhil is amused and lets him go. He promises to be back “by dark.”

After they leave, Cinhil asks Jeb to check in on his sons, and warn Tavis to be careful of offending Murdoch. Jeb speaks well of Javan. We find out Queen Megan is dead—according to the genealogies in the back of the book, ten years ago.

Cinhil is very concerned that his sons be prepared when he dies. Meanwhile Camber corners Joram outside and tells him about Rhys’ secret coded message. He decodes the message and tells Joram what it says: Rhys has found a way to shut off Deryni powers.

Exclamation point. End chapter.

Chapter 3 follows Jebediah to the royal nursery, somewhat later than he planned. Prince Alroy is still at his books, having failed to prepare his lessons, and Jeb suspects the punishment would have turned corporal if he hadn’t been there. Prince Rhys is playing (brilliantly) with toy soldiers. Javan is hiding in an alcove, and Tavis, who is a Healer, is working on his clubbed foot.

Tavis tells Jeb that Javan and his brothers spent the morning in a five-mile forced march in armor. Javan did well, but his foot paid a severe price.

Jeb is outraged, as is Tavis. Javan is plucky. He has to be strong, he says, to be “a warrior king.”

Jeb points out that Cinhil is not a warrior but is wise. Javan is scornful. His father is “neither prince nor priest, and accursed by God.” And Javan’s foot is the proof. Then he bursts into tears.

Jeb is horrified. Tavis is bitter—he’s not the one who taught the boy these things.

Jeb is left in a quandary. He has to tell Cinhil, and worse, Camber, that Javan’s teachers have been teaching him false and devastating things.

Camber meanwhile has reached Ebor with Joram and is pondering the message Rhys sent. At length. On multiple sides. Because that’s how Camber rolls.

Camber reaches the Earl’s bedroom, and gets filled in quickly and mentally. Camber questions Rhys about details, then reads Gregory and asks Rhys to show him what he did. Rhys goes in, turns the powers off. Camber investigates. Amazing! He and Joram check Gregory’s mind out thoroughly. No powers!

He takes a moment to shudder at the thought of such a thing being weaponized. He pushes that aside and brings Rhys in to turn the powers back on.

They’re all dumbstruck. Gregory, who has slept through it, continues to be a passive lab animal. Rhys takes Camber and Joram to another room, where they interrogate him as to what he did and how he did it. They discuss the ethics and the possibilities. Can it be done to an unwilling subject? Gregory was asleep and willing. Rhys isn’t sure he could have done it otherwise.

Evaine points out that if Gregory hadn’t been unconscious, Rhys might not have discovered it at all.

Because he’s been so far out of it, Gregory doesn’t actually know what happened. Rhys doesn’t want to tell him yet, either.

Meanwhile they have to decide what to do about Cinhil, who wants to see Gregory. Gregory will have to go to Cinhil—he’s not doing well. Rhys, when questioned, gives him at most a month to live.

Camber is shocked. Cinhil knows, he realizes—and is alone in Valoret without the Camber family to manipulate—er, help him. Jeb and Tavis can’t do what Camber needs to do before Cinhil dies, which is apparently to tell him the truth about the long con.

Camber has to get back. Rhys doesn’t feel comfortable leaving Gregory until morning. Cinhil won’t die tonight, Evaine insists.

That may be true, but Camber can’t stay. He has to go now. The others should follow when they can—and he prays they stay safe.

And I’m Thinking: Now this is more like it. After the endless droning synopsis of the previous volume, we’re back in prime Kurtz territory. Fast action, strong characters, high stakes. Chapter following chapter at a rapid clip. Excitement! Drama! Cool magical stuff!

The long gap in the timeline means we’re missing a whole chunk of development about the Camberian Council. And poor little Queen Megan gets killed off without ever really having lived.

But! Evaine is more of a partner in crime than she’s been since early in the first book, and she and Rhys are a formidable team. Their three kids are basically nonexistent; it’s not even clear where they are or who is looking after them (though maybe I read too fast to catch the reference).

But hey. Evaine is an actual person with actual things to say. And we do get to see the three princes. That, compared to the previous books, is huge.

It is actually authentically medieval for parents to be doing their thing and their children to be raised elsewhere. Medieval nobility fostered out their children for political reasons, and the parental bond we make such a virtue of was often not there. Young people bonded to their nurses and teachers (a bit of which we see here with Javan and Tavis) and maybe their foster parents. Their actual parents might be near-strangers. (That was true all the way to the Downton Abbey era—the servants had closer connections with the noble offspring than the parents did.)

So that’s a bit of real medieval in the worldbuilding.

I’m having a great time so far, and I’m happy about it. I was so disappointed in Saint Camber. This one is telling a real story in real time with real people. The character intros and the backstory are deft and quick and relevant—they’re well done. I like it.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, a medieval fantasy that owed a great deal to Katherine Kurtz’s Deryni books, appeared in 1985. Her new short novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, has just been published by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed spirit dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.